20 years ago, I wrote an article in this same column about the different ways financial institutions are compensated and their implications for consumers. Suffice to say, the industry, which is largely commission-based, wasn’t too happy with what I had written.

Over the past few months, in various media interviews, I was asked about this topic again, and noticed similar misconceptions about the compensation models of financial institutions and their advisers (also called representatives). And so, I thought it would be good to write about this once again, now with my views more matured through 2 decades of my practice and also travelling and learning from different countries.

The remuneration landscape

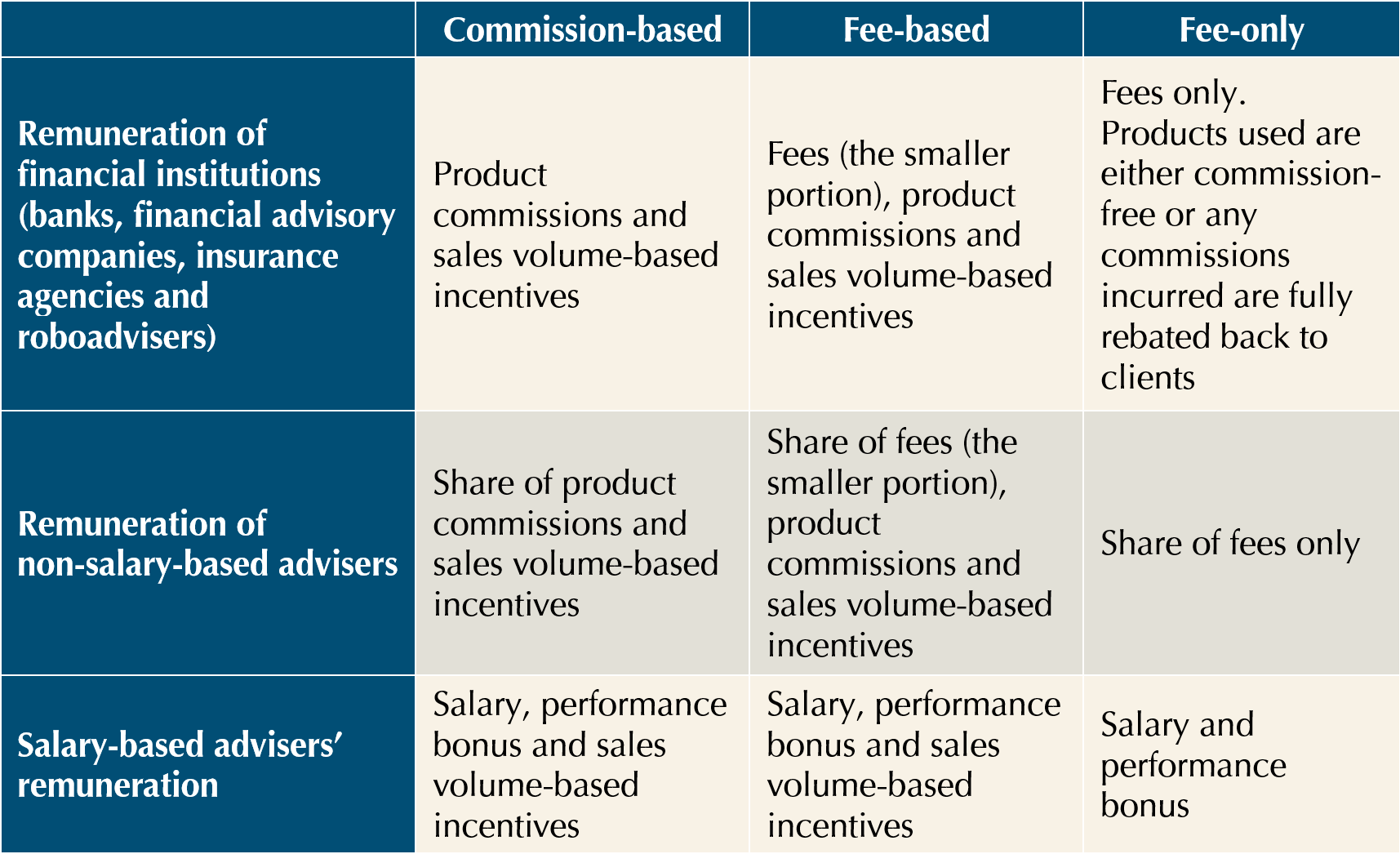

Globally, there are 3 ways financial institutions, and 4 ways individual advisers are paid (see table below). For the institutions, they are either commission-based, fee-based or fee-only. For representatives, besides the 3 ways as described above, they can also be paid a salary.

If a financial institution and their representatives are commission-based, it means that they are only paid a commission when there is a sale of financial products. Commissions can include, but are not limited to, insurance commissions, and brokerage or trail commissions from unit trusts. For fee-based firms, they charge clients a small fee for advice but get paid commissions when financial products are sold as well. Typically, fees comprise a smaller proportion of their total compensation. Finally, fee-only firms are compensated solely through fees paid by their clients. Unlike other firms, they do not receive commissions from product transactions, even if they provide assistance in executing them.

In all these companies, it is also possible that the advisers are not directly paid commissions or fees from their clients, but are salaried employees who may receive occasional sales incentives and a year-end performance bonus.

Understanding how advisers and their firms are remunerated is crucial because compensation plays a significant role in driving behaviour and can create a potential conflict of interest between clients and the advisory firms and their representatives. The topic of remuneration is so important that it is specifically dealt with in the Financial Advisers Act.

Till today, I maintain my stand that commission is the biggest source of conflicts of interest for the financial advisory industry. This is not to say that financial institutions and their representatives who receive commissions are dishonest. But it is simply a fact that if firms (whether commission-based or fee-based) are paid by product commissions, there is always that temptation for them and their representatives to recommend products that benefit them financially instead of what is best for their clients.

Even when advisers receive fixed salaries, a conflict of interest persists if their financial institutions earn commissions. Institutions dictate the product focus for their representatives and tie their employees’ incentives to sales, perpetuating the conflict.

I have personally spoken to many salaried advisers who admitted to this. So, does this mean that only the fee-only model is free from conflict?

Challenges of a fee-only firm

Even though I founded a fee-only wealth advisory firm, I have to say that conflicts still exist. The amount of revenue a fee-for-service firm and its client advisers make depends a lot on how much work is done for clients and the amount of assets it manages. Consequently, there exists a possibility that client advisers may engage in excessive work for their clients and recommend higher levels of asset investment than necessary.

But between the two (commissions versus fees), I find mitigating the conflict of interest for a fee-only firm to be much easier, and that is why I went that way in 2003. At Providend, once the scope of work is mutually agreed between our clients and us, the fee is fixed. Thus, even if we exceed the anticipated time budget, there is no increase in fees. In terms of products, we use zero-commission investment instruments wherever possible. However, if there are commissions from any product transactions that we cannot avoid, we rebate them back to our clients. Furthermore, the investment amount is not arbitrarily decided. Instead, using a transparent set of assumptions, we engage in a thorough analysis with our clients, based on their individual needs and requirements.

As a fee-only firm, our biggest limitation was that we were only able to serve affluent families until recently, when we finally extended our services to the mass affluent. We define the mass affluent to be clients who are likely in their mid-30s to mid-40s with at least S$350,000 investible or annual family income and the affluent to be families with S$1.5 million investible and above.

Although not the most robust approach, based on our extensive two-decade experience, we have observed that families with higher investible wealth often face more complex financial requirements that justify the payment of fees for quality advice. In these cases, opting for a fee-based model proves to be more cost-effective than relying on commissions. Conversely, younger individuals and families with lesser wealth typically have simpler needs, and it may be more cost-effective for them to engage commission-based advisers. However, it is crucial to ensure that these advisers prioritise the clients’ best interests, as poor advice can result in even greater financial consequences.

When I started Providend, my dream was to build a comprehensive wealth advisory company that was a professional service firm and not a sales organisation. That was why I chose the fee-only way. But over the years, we have found the commission-based approach to be viable for individuals with less complex needs. But companies and their representatives need to be transparent with their remuneration and put in place structures to mitigate any potential conflicts of interest.

Of course, how financial institutions and their representatives are remunerated is just one factor in choosing a suitable trusted adviser. Other factors, including how an advisory firm builds an advisory and not a sales culture, institutionalises its practice, deepens advisory depth, are also important considerations. You can read more about it here.

When I first wrote that article about how commissions can create an inherent conflict of interest between clients and their advisers, many advisers were unhappy and still remain unhappy with me to this day. Maybe it was how I wrote it, but if they can forgive my poor posture then, and acknowledge this conflict of interest and seek ways to mitigate it, it will benefit both our clients and contribute to the professionalism of our industry.

The writer, Christopher Tan, is Chief Executive Officer of Providend, Singapore’s first fee-only wealth advisory firm and author of the book “Money Wisdom: Simple Truths for Financial Wellness“.

The edited version of this article has been published in The Business Times on 19 June 2023.

For more related resources, check out:

1. Choosing a Wealth Adviser That Will Always Do the Right Thing for You

2. The Confession of a Financial Adviser

3. The Untold Story of Wealth Management and the Sale of Financial Instruments

We do not charge a fee at the first consultation meeting. If you would like an honest second opinion on your current estate plan, investment portfolio, financial and/or retirement plan, make an appointment with us today.