I have been racing sailboats since I was in primary school. I took a break from it in junior college, and then started again when I was at university. Now, when I can find the time and the opportunity, I still enjoy the occasional day out at sea, or friendly weekend regatta, usually at Raffles Marina in Tuas.

I know my way around a boat, but if I am honest, I am far from being the most knowledgeable or the most skilled sailor. Still, at times, I have found myself doing well enough to be leading a fleet during the odd race or two.

I enjoy sailing because it is a challenging sport in which we do battle not only with other sailors but also the elements and ourselves. In many ways, I have found sailing to be a good metaphor for life (and managing one’s wealth!), and I have had several experiences from which I have taken away useful lessons that can be applied both on and off the water.

The following is about one such experience.

Competitive sailing, in a nutshell.

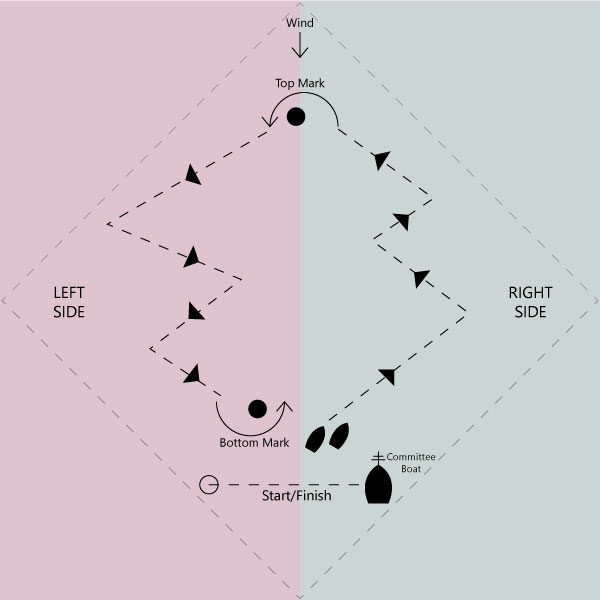

So that you may better appreciate the rest of this sharing, here is a quick illustration of how a simple sailing race may work:

- We start at the bottom end of the course (here marked “Start/Finish”), count down to the starting horn and try to cross the starting line at best speed.

- We cannot sail directly into the wind, so we move freely up through the roughly diamond-shaped course in a zig-zag manner known as “beating upwind”.

- We go around the “Top Mark” and then back downwind round the “Bottom Mark”, performing as many laps as is required before coming back to the finishing line.

- A regatta consists of multiple races which contribute to an overall score.

- One of the essential parts of sailing a good race is to navigate the course taking into consideration, among other things, the wind and the current.

- And because of the size of the course, it is often the case that the conditions favour one side over the other at any given time.

A very short racing case study.

During the most recent regatta I sailed (which unfortunately was one and a half years ago, largely due to COVID-19), my crew and I found ourselves at the front of the fleet right off the starting line and managed to maintain our position through two legs of the race. While going up the course for the second time, though, we made a mistake—a crucial error that cost us a good finish. We had gone to the right side of the course, while allowing most of the fleet to go left.

Why that was a mistake.

Although it is good to sail to the side of course we think is favoured, one of the rules of thumb often used when ahead in a fleet race is to stay on the same side as most of the other boats, or at least one’s closest competitor.

The logic behind this is simple. A win is a win whether we finish minutes or milliseconds in front of the second boat. If we are ahead and can ensure that our opponents never have the chance to benefit from conditions significantly different from us, it stands to reason that if we are sailing at least equally well, we can maintain our position.

On the other hand, if we split up, there is a chance that we pick the wrong side, and even if we initially choose correctly, there is the small possibility that the other side becomes favourable halfway, which may give our competitors valuable opportunities to close the gap, or even overtake us.

In this case, the wind ended up shifting to the left, and we finished in 5th out of 16 for that race, instead of in the 1st place.

Why we went right anyway.

We probably deserve a scolding from the coaches who had taught us how to race (what a rookie mistake!). Upon reflection, however, I think that we probably did what we did for two main reasons:

1. We had forgotten how winning was defined (in that context).

One of the key factors in leading us to make that bad decision was losing sight of our true objective. In the heat of the moment, we had been focused on trying to widen our lead, rather than simply finish ahead which is all that is needed to win. By trying to do better than required, we took an unnecessary risk that led us to fall short of our desired outcome.

If we had not gotten carried away and had managed to keep in mind that we just needed to stay in front, we may well have done much better.

2. We believed that we knew better than everyone else.

In our eagerness to pick the better side of the course, we had convinced ourselves that we had made the right decision, although it would later become clear that the rest of the fleet had seen something different. We had only tried to re-join them on the left side of the course when it was already too late. In fact, I remember thinking, “this side is better, why are they all going the other way?”

We had been overconfident and could have benefitted from realising that the sailors, as a group, had known more than each of us did individually.

Lessons that apply to wealth and investing.

When I took time to reflect upon what happened that day, I found that the learning points from that experience could be applied in a broader context. The pitfalls I highlighted above are not unlike some which arise in the process of managing our wealth, and I was reminded that it is extremely important to:

1. Remember what you want your money to do and why you are saving or investing.

As with remembering how winning is defined in a sailing race, it is essential that you have a clear idea of what winning means for you in your life and in terms of your personal wealth goals.

What do you want to achieve with your money?

Do you want to prevent erosion of your purchasing power by just beating inflation?

Do you want to create a comfortable retirement?

Do you want to leave your children with a significant gift sum when you can no longer be with them? Or all the above?

And importantly, how much is enough to realistically achieve what you desire?

Once you can answer these questions with some clarity, you will know better what kind of strategy you need to employ, and you can determine if you have already achieved, or are on track to achieving, the outcomes you want.

That is why it is important to have deep conversations about how you define success and to be able to transform the output of those conversations into concrete goals.

2. Recognise that it is extremely hard to predict the future and that there are significant costs to being wrong.

In sailing, it is true that it can be difficult to navigate tricky conditions and to get an accurate read on how the weather is going to behave, although very experienced sailors can still do it relatively well. Even so, it is a big risk to split from the fleet because being wrong can be very costly.

The financial markets are far trickier. Even among professional investors, a large majority do not outperform the benchmarks, and those that do are not usually consistent above what can be expected from random chance. It seems to make even less sense, then, for non-professionals to try to do so, especially for those who are already doing well financially, and when it comes to their most important wealth goals.

In wealth planning practice.

These are two key reasons why, at Providend, we believe in creating wealth plans that are in line with the principle of sufficiency, and that how much risk you take with your money should be determined not only by your ability and willingness to take on such risk, but also your need to do so.

Taking unnecessary risks by attempting to time the market, or by trying to pick hot stocks, fund managers, sectors, or regions, instead of holding a well-diversified, evidence-based portfolio with an appropriate asset allocation can jeopardise rather than further your wealth building endeavour.

Many of our clients have been fortunate enough to have had their hard work and diligent saving pay off in a way that may well have already put them in a good position to reach their wealth goals without having to take huge risks. They are ahead of their fleet (read: goals) and thus, protecting their position should be a major priority—because the truth is, they only need to stay ahead and finish well to win.

Me and my team leading a race

at the 22nd SMU-RM Western Circuit Sailing Regatta.

This is an original article written by Bryan Chan, Associate Adviser at Providend, Singapore’s First Fee-Only Wealth Advisory Firm.

For more related resources, check out:

1. Moods and the Market: How to Invest and Keep Investing

2. My Realisations of What Wealth Planning Is Really About

3. How to Build an Affordable Diversified Portfolio?

We do not charge a fee at the first consultation meeting. If you would like an honest second opinion on your current estate plan, investment portfolio, financial and/or retirement plan, make an appointment with us today.